by Sumana Roy

The career of the “literary” has not been very different from the Brahmin’s protectionism of the mantra, an inheritance kept out of the reach of the non-Brahmin. One of the ways in which this has been done in the last hundred years is through anthologies that create — and reiterate — the idea and the habitat of the literary.

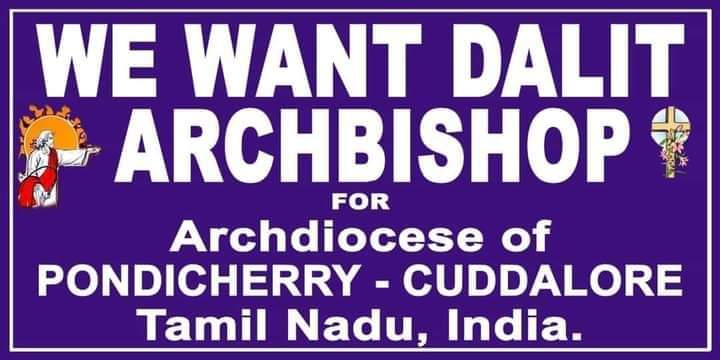

A few months ago, when the Bengal Chief Minister announced the creation of a Dalit Sahitya Academy, many rushed to characterise it as another of Mamata Banerjee’s “minority appeasing” policies. It was even turned into the likeness of a joke — that there should also be a Brahmin Sahitya Academy, and so on. Raised by parents who rarely discussed caste, and an education system that refuses to engage with it except in a nominal way, I crossed over into adulthood without the awareness of caste marking my thoughts, choices and decisions. All of this would not need to be said if it hadn’t informed the reading choices of people such as myself. It couldn’t be a coincidence, could it, that my favourite writers in Bangla were upper-caste writers, usually Brahmin, or that Bangla literature was Calcutta-centric? This, it seemed, was no different from WASP literature providing the only understanding of the literary in the Anglo-American world. By Brahminical, therefore, I mean an attitude, and, consequently, an invisible structure that makes the normative seem normal, and everything else just aberrations — the way, say, “General” seems to be normal, and “SC/ST/OBC” exceptions, or heterosexuality taken to be the norm, and other sexual orientations wayward.

That what we assume as literary is partly a result of our location in the various social structures we inhabit is never quite acknowledged. Just as having tea with salt and butter in a Tibetan household does not quite feel like tea to my sugar-and-milk-knowing tongue, anything outside the range of familiarity — of its tone, register, aesthetics and politics — of the “literary” seems foreign, even contraband, and is, thereby, rejected. This hierarchy, inevitably deriving from arbiters who hold political and economic power, seems to decide what constitutes physical beauty, the singing voice, correct pronunciation, education, manners, handwriting, propriety, or even what constitutes food.

The literary can behave like a gharana, and it is the nature of gharanas to keep things unlike it outside its fold. The “literary” has been inevitably phallic. It was this narrow sense of what constitutes the literary that Virginia Woolf was challenging in A Room of One’s Own — of the genius, which we imagine as inevitably male, and of “anon”, the anonymous (female) creator of primarily oral literature; of the novel, that she asked women to make their own, because it was still a new form, unlike others which had become solidified into male genres. It was also to expand the idea of the literary that Rabindranath Tagore argued for in his introduction to the stories for children in Thakurmar Jhuli. There are two pieces of irony here: Tagore, now a totem of the literary, was once rejected for not being literary enough by Calcutta University; his name, turned into the adjective Rabindrik (“Tagorean”), has been used by the establishment to keep out singers who are disobedient to the Visvabharati mode of singing.

The career of the “literary” has not been very different from the Brahmin’s protectionism of the mantra, an inheritance kept out of the reach of the non-Brahmin. One of the ways in which this has been done in the last hundred years is through anthologies that create — and reiterate — the idea and the habitat of the literary. Indian English poetry, as a field for instance, was created in the same manner. Different as they might be in style and temperament, there is something that is common to them — their metropolitan location. With the exception of Jayanta Mahapatra, the poets in these anthologies are from the metropole, so much so that it might seem that Indian English poetry was only a Bombay phenomenon. The indifference of the anthologists to circles outside their own, unless the poets had a reputation buttressed by the West, as in the case of Mahapatra, who won a prize given by Poetry magazine, created an idea of the Indian English poem that was influenced by the prevalent literary climate in America and England.

The lack of inclusion of the provinces, of poets whose writing had been formed by their other languages, was responsible for a monolithic understanding of the Indian English poem. To ask a question like “Why was there only a woman or two in these anthologies?” is not to ask a question about representation. It is to continue to argue, after Woolf, for increasing the perimeter of the “literary” to include those whose writing have not been included in the idea of “literary history”. The Indian English poem in these anthologies, male in form and tone and urban in its sense of power, supplied the idea of the “Indian English poem” for decades.

Like inter-caste marriage that supposedly kept Brahmins pure, editors keep the circle of contributors limited to family and friends. One only needs to pick up an anthology of Indian English anything — essays, poems, stories — to confirm how the literary is a baptised name for a family-and-friend enterprise, a taste and manner that is feudal, and which its practitioners believe is superior to those that have been excluded. What that has enforced is the idea of a literary that is aspirational, not completely unlike a “posh accent”. The literary has forced a homogenisation of literary production — everyone must write within its aesthetic range to be considered literary writers. Reviewers, because they come from the same class, become naturalised citizens of the world of literary gatekeeping.

“Decolonising the syllabus” is a demand to expand the idea of the literary, not in an instrumental and bureaucratic manner, but of its monolithic real estate — it is a rejection of its proprietorial and gatekeeping behaviour. What the “literary” needs, however, is not the erasure of what once constituted it — as some cancel culture advocates demand — but a far more inclusive accommodation of writing; not a UN-like representative model of writers of various constituencies alone, but of various kinds, manners, and forms of writing.

It is time for the literary to lose its sacred thread.

This article first appeared in the print edition on December 19, 2020 under the title “Read, without the sacred thread”. Roy is a poet and author.

Credit: The Indian Express