By John Dayal

Exactly seven decades on, the Dalit Christian does not seem to be winning her, or his, a battle for human dignity, political rights, and a level playing field. And it is not surprising that this is so, for the Christian of Indian Dalit origin fights a battle on three fronts, unaided, with few resources, no allies, and armed with little more than in the justness of the cause.

The first front is against the Constitution of India by law established, as they say.

The Presidential Order of 1950 devastated the new-born Constitution of India far more severely than could have been imagined by its makers, who had laboured more than two years through the bloodshed of a religion-based partition of the land which possibly left a million men and women dead, many more raped and maimed, and millions forced to migrate to the safety of a Muslim majority Pakistan, or a large Hindu, but still secular, India.

Despite the trauma and the memories, the Constitution promised secularism, respect for all religions, and opportunity. Above all, it guaranteed to the Dalits freedom from their bondage, equality they had been denied in the Code of Manu three thousand years ago, and a say in governance through reservations in the political process, from the grassroots to the Parliament of India.

The 1950 Order, later made permanent as Article 341 part 3 of the Constitution, told the Dalits they had no freedom of choosing their faith. They had to remain Hindus if they wanted political rights, economic and educational rights, and special protection of the law from the brutality of caste vindictiveness, abuse, and violence. It is still so. Most people cannot imagine how this could have happened when Jawaharlal Nehru, an agonistic liberal, was prime minister and Baba Bhimrao Saheb Ambedkar, chair of the Constitution-making committee, was the minister in charge.

It brings no credit to the freedom-loving but casteist members of the ruling party and others to have second thoughts, to keep their erstwhile vassals in control, and to build a barrier against philosophical and theological challenges by liberal religions, not just Christianity and Islam as one would think, but the revolutionary dictum of Buddha and the modernity and equality of Sikhism. It would take Sikhs and Buddhists decades of struggle to regain their rights.

Even then, the price they had to pay was to dilute their identity as distinct religions and to be counted under the umbrella or shadow of the majority Hindu definition. That too would have repercussions, bloody ones, later.

Ambedkar himself became a Buddhist, fulfilling his prophesy that he would though born a Hindu, not die as one. The Sikh’s identity struggle is reflected in the often blood-soaked politics of Punjab.

For the Dalit Christian, the legal battle to undo Article 341 part 3 continues in the Supreme Court, with little indication that something concrete will come from it in the near or middle future. The current political dispensation, like, the ones over the last 70 years, are loath to shed the hegemony of the upper castes, and afraid they will open the flood gates of an exodus seen in religious history. The Article is, in reality, a nation-wide, powerful anti-conversion law. It is a big deal.

The second front of the battle for justice is with the Dalits who are forced to remain Hindus, and now neo Buddhists and Sikhs. The governments and the upper caste political parties – and that means every party other than those professing Marxist ideology – have been successful in persuading the ‘Dalits Hindus’ to believe that the Christians, arguably better educated, would eat away their piece of the cake, take away their jobs, their scholarships, and their opportunities.

This is a ridiculous argument. The cake is not finite. A stronger political presence can enlarge the cake. The Christian Dalits face the same social infirmities, as caste discrimination is in the very soil of India. A judicial inquiry has confirmed what sociologists have always known. Caste discrimination, casteism, is osmotic; it crosses barriers of religion and even of ideology. But so deep has the belief been ingrained that the biggest resistance comes not from the upper caste leaders, who remain in the background – but from the Dalits in the Hindu frame.

How will the Dalit Christian ever convince his brother in the Buddhist, Sikh and Hindu faith that he means no evil, that the political field will be strengthened, and that collectively the community would progress? The Dalit Christian leadership is still not educated in the refined political action that is required. There is no real effort at the collective building of civil society, or sharing of resources, supporting the educational effort, and other visible confidence-building measures, as they are called in diplomacy.

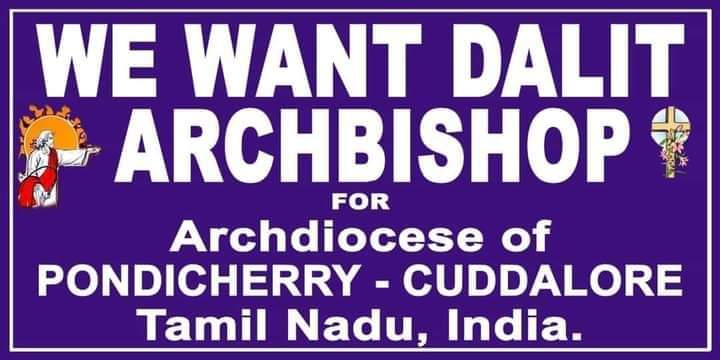

But, of course, the final frontier is within the Christian church, the Christian community. Ethnic-based churches, denominations and Rites, are singularly ill-equipped to even begin understanding the situation. Into the third decade of the 21st century, the “Christian” region of the Northeast, as well as the Christian belt of the west coast from Gujarat to Kerala, has not only no clue as to the situation but at the grassroots, is resistant to the idea of treating the Dalit Christian as an equal, much less joining him in the struggle for constitutional rights. Ethnic memory and the pride of upper caste origins, real or imaginary, sharpen this divide. Theological boundaries, especially as professed by certain evangelical and Pentecostal groups, range Christ himself against the Dalit struggle, disowning their very existence in the community as an aberration, if not an act of blasphemy against the Word of God.

In the “political leadership”, in reality, people of Christian birth who rise to positions of political power based on family, land, or local concentration, as in central Kerala and parts of Karnataka, do not feel they owe anything to the community outside their constituency. Parliamentary debates are evidence of the silence of the representatives.

The religious leadership pays little more than lip service, going by four decades of a study of the situation on the ground. At their best, they are embarrassed that caste exists in the community. This writer was in court when the chief justice of the day, a Dalit, Justice K G Balakrishnan, asked the counsel of the Christians if the Bishops would say caste was still practiced in the church and the community. It was a Catch-22 situation. The community chose to fall into the trap by maintaining silence. It would have been possible to say they were ashamed to admit that it, in reality, it did exist. The moment was lost. Forgetting that truth would set them free was expensive. And perhaps morally degrading.

The community had to struggle for decades before persuading Rome, and the Anglicans at the Lambeth conference that caste discrimination existed even if the walls in the Tamil cemeteries were theoretically erased on paper.

The last three Popes have been vehement in giving a tongue lashing to Indian Bishops, telling them to eradicate all vestiges of casteism. Pope John Paul II in his many addresses to “ad limina” visits of Catholic bishops from India told them that Christians must reject divisions based on caste, saying such prejudice “denies the human dignity of entire groups of people.” He had first made such a statement during his 1986. The pope said caste-based prejudice violates “authentic human solidarity” and is “a threat to genuine spirituality.” “Customs or traditions that perpetuate or reinforce caste division should be sensitively reformed so that they may become an expression of the solidarity of the whole Christian community,” he said.

The single visible movement in the church is the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India’s policy document on Dalit empowerment, in which it acknowledges centuries of caste-based discrimination as a ‘grave social sin’ and commits to ensuring that the practice of ‘untouchability’ will not be tolerated within the church. “I wholeheartedly urge the Bishops, priests, religious and lay leaders to internalize and implement the policy at all levels. We should consider it as our obligation based on Christian faith to empower our children, sisters and brothers of Dalit origin and other marginalized people,” said Baselios Cardinal Cleemis, Major Archbishop-Catholicos and President of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India.

As has been reported in media, the ‘Policy of Dalit Empowerment in the Catholic Church in India: An Ethical Imperative to Build Inclusive Communities’, issued on December 13, 2016, includes commitments such as ensuring that Dalits are given equal employment opportunities; more competent and cohesive lay leadership development for Dalit men and women at regional and diocesan levels in the Church; dedicated funding and scholarship structures to assist marginalized Dalit students to further their education and to facilitate the Dalit community’s access to social justice.

This writer had welcomed the document as a powerful commitment to a seminal struggle against birth-based discrimination that corrodes human dignity.

But there are few, if any signs, that the document has been implemented in the Catholic Church in letter, and spirit. Perhaps a survey would expose the hollowness of official claims.

But then the church, all denominations, has so far fought shy even of a simple economic and social situation survey often community. Such data would have quipped them better in their discussions and negotiations with the government, and their arguments in court. The only studies have been by outsiders, and they are based on dated empirical data.

Information and data is power, even political and legal power. It is time for the community and its leadership to case ranks, admit their faults in the Christian spirit. Despite untouchability being outlawed, many in the Hindu community still practice it in everyday life. But the reform movement is also strong.

The church in India also needs a powerful reform movement against vestiges of untouchability and discrimination that are sapping its strength from within. Without this, there can never be real and meaningful solidarity with the struggle of the Dalit Christians.

[John Dayal is an author and activist. He is a former president of the All India Catholic Union, and a member of the National Integration Council.]